By Stephanie Clemens

Prelude

In 1988 Momenta Dance Company decided to honor Doris Humphrey, one of the great pioneers of American Modern Dance. Humphrey was born in our home town—Oak Park, Illinois. Our first concert featured Humphrey’s “Air for the G String” from 1928 and “Soaring,” a work Humphrey choreographed with Ruth St. Denis in 1920. Both works were set through services of the Dance Notation Bureau. This decision prompted Doris Humhrey’s son, Charles Humphrey Woodford to come to Oak Park to see the concert.

Grieg Concerto

Shortly after meeting Charles Woodford, I got a call from Charles who said he thought we would be the company to work with Eleanor King on reconstructing Humphrey’s 1928 “Grieg Concerto” (also listed as “Concerto in A minor”). It sounded like an exciting project, a big work calling for 15 girls and a strong female soloist. It also called for a rather large set of tall screens and a platform. We agreed and felt it would be an extraordinary experience to work with Eleanor King, one of the original cast from 1928. We contacted Eleanor and flew her in from Santa Fe. I met her for the first time, at O’Hare Airport in Chicago—she wore a white fur hat and coat. In greeting her, all I could think to say was “You’re tall!” Without missing a beat, her bright blue eyes twinkled as she said “But so are you dear!”

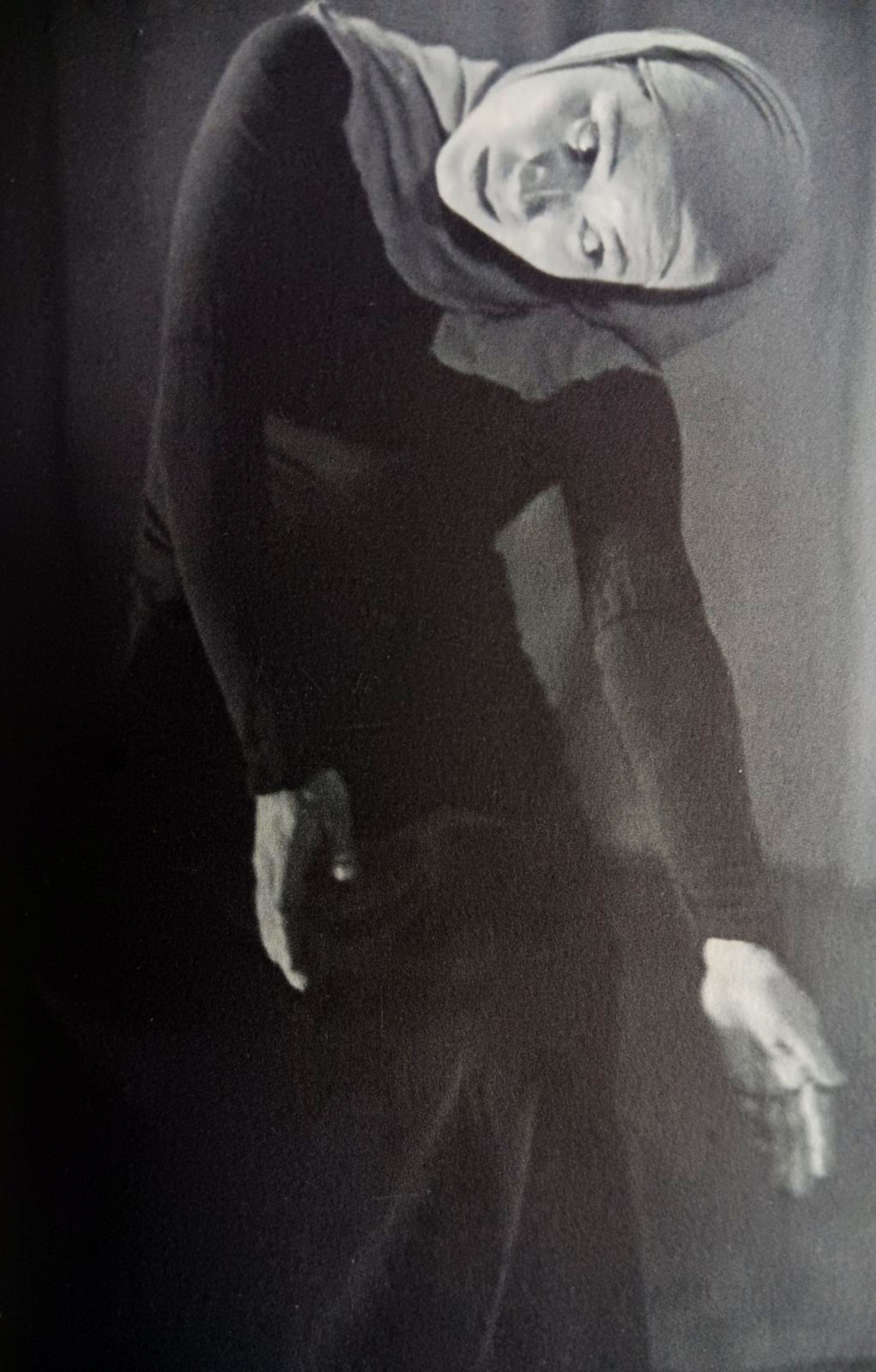

We started the following day, with a cast of students—some as young as 12—a few young adults, and a fine soloist, Laura Schwenk, who had danced with Pacific Northwest Ballet. Unfortunately none of our dancers had experienced Humphrey-Weidman technique—and Grieg was a work that was a strong statement of successional movement and fall and recovery, hallmarks of Humphrey-Weidman technique. Eleanor had her work cut out for her—not an easy task at any age, but she was then in her 80’s and was a cancer survivor. She taught us how to do side falls, front falls and spiral falls—difficult movement that she demonstrated herself. However, when the music started, it was amazing to see the muscle memories ignite this elderly woman’s frail body – the thematic statement of the work was a strong and forceful succession.

Eleanor’s memory for the architecture of the work was astonishing and in a few long, hard days, it took shape. Larry Ippel, Momenta’s Co-Artistic Director, built and painted the screens with gold gilt on terracotta photo paper and supervised construction a platform with some volunteers. We sewed costumes—black for the soloist, russet for the corps, and made a long red scarf for the soloist.

Charles Woodford came for the first performance in 1989 as well as Madeline Nichols who came to see if the reconstruction of Grieg was ready to be notated. They were encouraging but said it wasn’t yet ready to be notated.

I asked Charles if there were a Humphrey Foundation that could provide funds for further work on the project—he looked at me and said “No, why don’t you start one?!” I replied that I would only if he agreed to be the President—and so we created the National Doris Humphrey Society.

Shortly after Charles brought Ernestine Stodelle to Oak Park and we began Doris Humphrey Technique workshops that were annual for many years.

Touring with Eleanor

Momenta continued to expand its repertory of Humphrey works and our dancers went on tour to Washington DC, NYC, and SUNY Purchase and Brockport with the American Repertory Dance Theatre directed by Mino Nicholas. Mino had worked a lot with Eleanor in reconstructing “Duo Drama,” “Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejia” and “Dionysiaques”—but while on tour he asked me to take Eleanor to lunch during tech and dress rehearsals as he did not want to hear any more corrections. Eleanor was very frustrated.

Tribute Concert — 1991

After returning from a tour that had been challenging, I had come to realize that Eleanor was not only someone with a great memory of the Humphrey works, but had had a long life as a creative artist, studying works by Native American tribes, and going to Japan to study dance theatre. She had choreographed a very sizeable body of work, primarily solos, that were quite brilliant. Momenta proposed dancing a tribute concert to Eleanor featuring “Roads to Hell,” “Mother of Tears,” “To the West,” “Air,” “Brahms Study” and “Enthusiasmos;” we invited Lori Belilove and Andrea Mantell Seidel to perform, each on a separate weekend.

It was an honor to have Eleanor coach “Mother of Tears” and “Pride” and “Sloth” from “Roads to Hell.” She gave me a lot of suggestions and corrections that helped to build the inner scripts that must inform the performances of her works. Choreographed in the 1940’s, “Roads to Hell” was a marathon of four challenging solos that Eleanor performed by herself— “Pride” was based on the character of Mussolini, “Envy” was a depiction of political mud-slinging and hatred, “Sloth” was no less than an embodiment of the United States’ reluctance to commit to join the Allies in WWII, and “Wrath” began with the dancer in a pose using her hands to depict the Chinese ideogram for rage. Each solo is a catharsis going from a position of power into a disintegrating impotence.

At the tech rehearsal for the first weekend, Eleanor was standing talking about colored gels for the lights and she suddenly collapsed and fell—there was a loud snap. We had to get EMTs and Eleanor’s hip was broken. She was admitted for surgery. We performed in her honor, and Andrea, a long time friend, was able to visit with Eleanor. By the second weekend, a doctor friend signed her out for an evening of “therapy” and Eleanor arrived in a an ambulence. She was dressed in a magnificent Japanese kimono, and enjoyed the concerts and attended the reception. She received quite an ovation that evening and was able to visit with Lori Belilove. The ambulence returned her to the hospital. After a week or two she was able to fly to The Actor’s Home in New Jersey where she lived. The day after her return, she was standing talking to a friend about the wonderful concert, and her heart fibrillated and suddenly, she was gone.

Eleanor’s Memorial

Later there was a Memorial dance concert in the Taos Ski Basin organized by Ann Mumford, Daniel Lewis and Andrea Seidel. Ilene Evans and I were Momenta dancers invited to perform. I danced “Sloth” and “Mother of Tears,” but before I went on, I asked Eleano’s spirit to guide my steps. I don’t remember dancing, but Danny Lewis said it was fine.

“Grieg” — reworked by Ernestine Stodelle

In the 90’s Grieg was shelved until I finally persuaded Ernestine Stodelle to see if she could bring it back to the stage. In 1997, she agreed, and our dancers, by then had studied Humphrey-Weidman technique for several years. Where Eleanor remembered the architecture and the steps, Ernestine remembered the intention and realized that it was a dance of power. Ernestine and Eleanor had both danced in the premiere, were members of Humphrey Weidman’s Little Group along with Letitia Ide and José Limón—they were also close friends and called each other Antigone and Iphigenia. Together they had remembered for notation “Water Study”—they had danced in it in 1928, and their version is longer and more architectural than the version Doris worked in at Juilliard in the last year of her life. The Doris Humphrey Society contracted with the Dance Notation Bureau for Jessica Lindberg to finally notate “Grieg Concerto.”

In later years, working on Denishawn repertory with Karoun Tootikian, we had verification of the choreographic elements that inspired Doris Humphrey in “Grieg Concerto”—Doris had collaborated with St. Denis on the 1920 “Sonata Pathetique” and seeing the works side by side, as we did in a concert in 1997, the strong diagonals for the leader with the followers are clearly related to Grieg—and the basic thematic movement of Grieg was the theme movement in Doris’ first dramatic solo as the Queen of the Underworld in the 1923 ”Ishtar.” Eleanor King’s architectural and muscle memories were correct.

During the time I worked with Eleanor King, we spent of lot of time together. While in Oak Park, she stayed in our home. She was an artist with a consuming quest for knowledge—even as a patient in the hospital, she asked for books on Japanese Architecture—and for ouzo, guacamole and beer and Peking Duck—all of which we smuggled in. In our time together, it seemed to me that behind her beautiful blue eyes was not only a lifetime of learning, but the insatiable spirit of the young girl who had danced with Humphrey-Weidman sixty years before.

For those who want to know more about Eleanor King, I recommend her book:

Transformations: a Memoir by Eleanor King of the Humphrey-Weidman Era. Published by Dance Horizons.

Eleanor King: Sixty Years in American Dance. Edited by Nicole Plett, Moving Press, Santa Cruz, New Mexico,